In my December 6 entry, I discussed how the 1984 famine was a man-made construct, rather than a result of drought only. Contrastingly, averting famine is a political choice. In this entry, I will discuss how the political decisions to invest in water management strategies in Tigray, helped avert famine. To conclude my findings on Tigray, I will also discuss what the situation with regards to clean water access looks like today, and how this is similarly shaped by national politics.

Policy Changes and Water Management Strategies

|

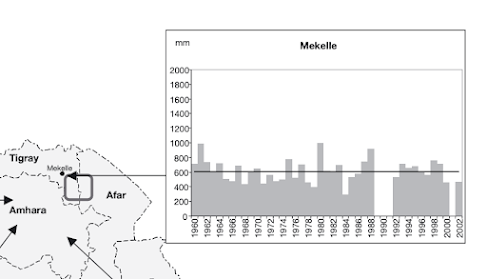

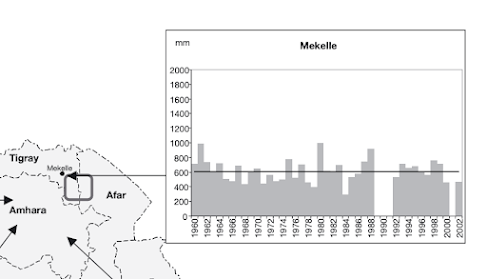

| Annual rainfall data from a rainfall station in Mekelle between 1960 and 2002. The solid line represents the 1971–2000 mean. Missing bars are missing data. Source: Meze-Hausken (2004) |

The new government responded by introducing a program of micro-dam reservoir construction across the north. These would be constructed by local communities with a 'food for work' scheme, paid through development aid and government grants. There was a strong participation of women in the workforce.

One of Tigray's micro-dam and irrigation projects, photographed by my mother in 1998.

Water Access in Tigray Today

Since early 2000s, wells and water projects were introduced in rural areas across Tigray by NGOs. These were intended to provide potable water to households, and also intended to lower the burden on women and girls who are traditionally the main collectors of water and firewood. While some notable improvements have been observed with regards to water quality, due to the sparse nature of settlements in Tigray, women had still had distances to collect water from the nearest sources. Often this task is time consuming and arduous as heavy 5 litre jerrycans are carried long distances. While the government's focus regarding water and food was to support rural livelihoods, urban areas also implemented water plants often equipped with generators and electric pumps. However on November 2020, the Tigray region was engulfed in war. Electricity was cut from the region and making energy-powered water sources inoperative, and water collection in rural areas too dangerous.

|

| A young girl walking home after collecting water in a jerrycan, photographed by my mother in 2012. |

Conclusions

The role of politics in water management and usage was highlighted during the 1990s when Ethiopia made policy changes that focussed on water conservation and irrigation for crops in drier months. By contrast, today's violence in Tigray has led to a multiplicity of devastations to basic services, and highlighted the nexus of water, energy and food.

Water stress from natural drought and destruction of infrastructure have the potential to lead to food insecurity. However, political and governance failures have repeatedly led to famine outcomes. Tigrayans today lack international attention to their plight unlike the 1980s. Today's crisis is happening in the dark away from the gaze of the media as the Ethiopian government has successfully blocked all means of communications to the region.

If we want to avert further tragedy and see a sustainable Tigray and Ethiopia again, we must learn that politically-motivated acts only lead to destruction. There is hope that guns have been silenced with the recent Peace Agreement. However, the real act of rebuilding must begin by ensuring basic services are restored to all people in the region. East African men in positions of power, from all sides, must be accountable. Reparations to survivors start there.

Comments

Post a Comment